“Preservation Future Tense” was the theme for Oklahoma’s 29th Annual Statewide Preservation Conference held in Oklahoma City. In partnership with our State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), the Oklahoma Main Street Program invited James Lindberg, Senior Director of the Preservation Green Lab (PGL) to speak at the closing Plenary Session. Since 2009 PGL, a part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, has authored some of the most current and forward-looking sustainable preservation research ever done.

Tearing Down and Rebuilding New to Save Energy and Money Has Been Debunked

Through reports such as The Greenest Building: Quantifying the Environmental Value of Building Reuse, PGL has outlined how historic preservation contains an incredible opportunity (nationwide) to enhance our efforts toward energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. Along with decreased lifecycle energy use, the “Greenest Building" report further outlines how upgrades and whole building energy efficiency retrofits have a better return on investment (ROI) than the newest “green” construction immediately. In fact, it takes between 42-80 years for the total lifecycle energy consumed by a brand new, modern, green, mixed-use building to fall below that of a historic Main Street building that was retrofitted to perform similarly. For historic houses the time frame is more like 38-50 years. See chart below.

From: "The Greenest Building: Quantifying the Environmental Value of Building Reuse", by Preservation Green Lab of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, page 9

We Don't Build Them Like We Used To

We previously discussed how historic vernacular architecture and existing buildings are already green because of their lighter environmental footprint (embodied energy/avoid impacts), high quality materials and craftsmanship, superior location for walkability, and the financial freedom they afford. The also grant the owners to take part in the shared history of their community, and that can be a lot of fun!

Even with all the positives related to historic and existing properties, many people want to learn how to improve their bottom-line and decrease their negative impact (carbon footprint) on the planet even further. Reducing the operating energy required to heat, cool, and provide electrical services to a building is how this is usually achieved.

Historic and existing buildings might have great bones, but almost always lack basic thermal control. Basic weatherization, composed of insulation and air-sealing, has a large immediate impact on energy use, and a great ROI. Beyond the basic, low-tech energy retrofits like this are a progression of retrofit stages you can follow to improve whole-building energy performance. According PGL, many commercial building owners have achieved upwards of 20 to 60 percent energy savings in historic, mixed-use Main Street buildings.

Feeling Lonely, Cheap, and Bored...

Today, as well as 50 years ago, we are falling progressively deeper into the clutches of the modern, high-tech mindset. We have inherited a more solitary, homogenized experience because of architecture today. We need to reconnect with the natural world and other people in real time, and in real life.

We used to build homes with porches and engage in the spaces outside the home - until the air-conditioner and color television brought us inside. We used to live in homes with style and neighborhoods with character, until the creation of cookie-cutter mono-block development was economized further by mass production and cheaper materials. Ceiling heights are 8'-0", and functional, long-lasting have been replaced with stylish and cheap. Consider plumbing and door hardware.

A Sustainable Continuum: Original Green vs. High-tech Green

We will get into the stages of how to implement a whole-building energy efficiency retrofit next time. But right now let’s visualize the inherent changes in the sustainable design of buildings over the course of time.

Historic vernacular traditions developed in a community because it was was the most sustainable way to build at the time. The ease of construction and cost-to-benefit analysis actively shaped the development of the style and form of buildings. In today's day and age we think much the same, but our resources are much different.

"Original green" is associated with historic vernacular architecture. Paying attention to how a building was set on the site was an easy, low-cost way to capitalize on passive solar heating and orientation with prevailing wind patterns. Buildings were also constructed of materials that were economical to transport and erect into the final building form. Sod houses and log-cabins are different examples that come to mind here. High ceilings and windows provided passive means for letting heat escape in southern climes. And, the technology of early days may have been as humble as panes of glass or a kerosene lamp.

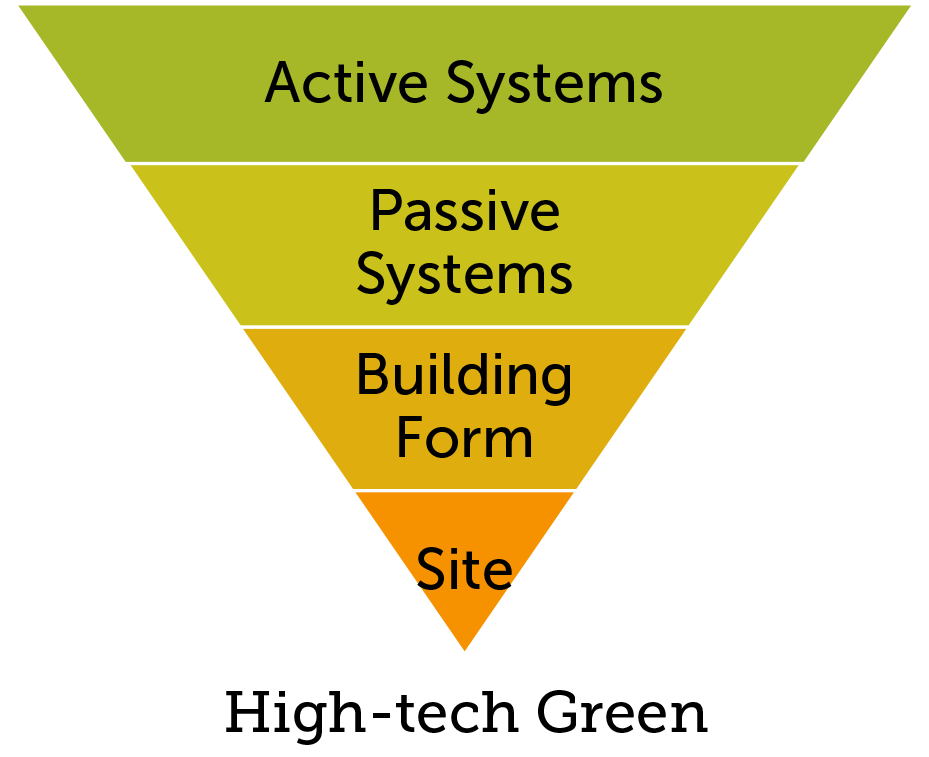

"High-tech green" might be seen at the opposite end of the spectrum, but not so fast. Our modern vernacular has shifted. Building materials are no longer regionally specific and yesterday’s high-tech materials (fiberglass insulation, engineered lumber, et al.) can be seen in our common, everyday buildings. Some of these materials that have been developed over the years have been “keepers” while others have been replaced with better options and newer technologies. Computers and “smart” systems have been developed and have removed a lot of the direct action from active systems. So are buildings skinned with solar panels, and large areas of glass truly the latest and greatest?

Even though the diagrams appear to be opposites, it is important to consider the differences between "original green" and "high-tech green" as a sort of continuum, or a sliding scale. I would even suggest that the mean between the extremes might just be the right place for sustainable architecture today.

What do you think?

Questions for you:

1) If you had too, would you rather live in a home without electricity or running water?

2) What modern building technology(s) are most exciting to you?

Share this post with a friend!